The Twenty-First Art Bulletin (November 2025)

Listen to ‘Ya Habib’ by the Palestinian band Darbet Shams, which includes the lyrics, ‘Come back, you will be safe. Don’t believe them and don’t be afraid. We will build our homeland’.

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 181, which set the stage for the Nakba, an act of ethnic cleansing that seized 78% of Palestinian land, destroyed more than five hundred towns and villages, displaced more than half of the population, and led to the creation of the State of Israel. Seventy-eight years later, the struggle for liberation persists as Israel’s escalated genocide continues to devastate Palestinian life. Across this long arc of dispossession and struggle, cultural work has been central to Palestinian resistance. For instance, a tradition of resistance literature, or adab al-muqawama (أدب المقاومة), rose from the ashes of the Nakba and has sustained Palestinian identity, documented colonial violence, and mobilised international solidarity. Wisam Rafeedie is one of the many writers who have contributed to this tradition. His novel, The Trinity of Fundamentals, first published in Arabic in 1998, offers profound insights into revolutionary subjectivity, political commitment, and the role of culture in national liberation.

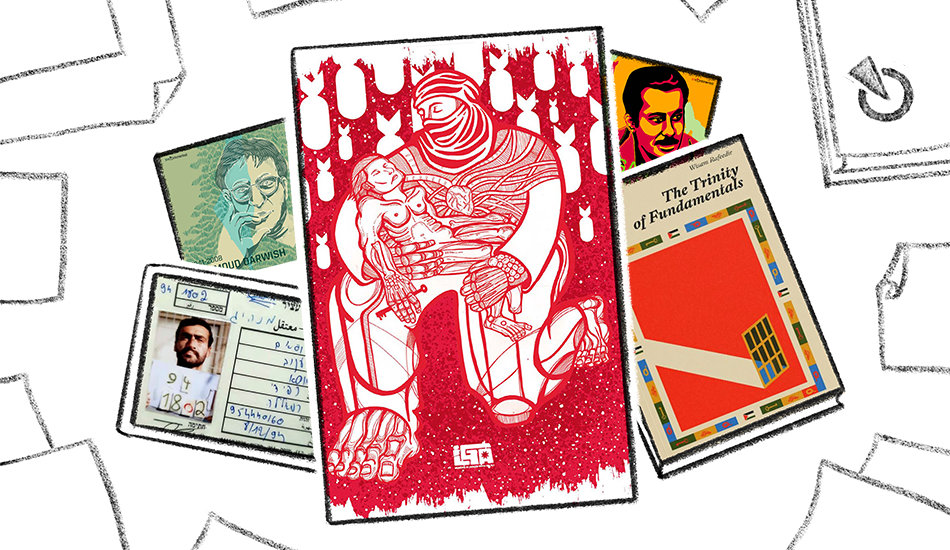

Published ahead of the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People on 29 November, the same day that Resolution 181 was adopted, this art bulletin examines the tradition of militant Palestinian literature through Rafeedie’s work and the recent English translation of The Trinity of Fundamentals (2024) by the Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM). Drawing from an interview with Kaleem Hawa, a Palestinian researcher and organiser with PYM, we explore how resistance literature has functioned as a weapon in the struggle for Palestinian liberation.

The Role of Palestinian Resistance Literature

Wisam Rafeedie’s Israeli prison ID card.

Palestinian resistance literature emerged from the conditions of Zionist settler colonialism backed by Western imperialism. Hawa explains that Palestinians theorise these conditions ‘as having at least three specific predicates: land alienation for primitive accumulation; population substitution, or ethnic cleansing; and a racial regime that produces segregation and organises society on the basis of Jewish supremacy’. Because Zionism wishes to instill ideological defeat, culture plays an important role in resisting these predicates. Palestinians fight back through a literature which conveys their political commitment, or iltizam (الْتِزام), and which might include sharing strategies for land defence. ‘Our cultural production also has an “offensive” function’, Hawa notes, ‘that is to counter Zionist propaganda, expand the base of popular struggle, and build enduring international solidarity’.

Against dispersal and disarticulation, culture binds Palestinians together around shared traditions and stories. Ghassan Kanafani, a Palestinian writer and member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), popularised theories of resistance literature. Assassinated by Israeli forces in Beirut on 8 July 1972, Kanafani understood resistance literature as a form of cultural production emerging from peripheral social formations engaged in the national liberation struggle. This literature spoke to the realities of the Palestinian subject in conditions of dispossession and reconstitution. For Kanafani, resistance literature was a literature of political commitment in the tradition of Arab iltizam. Its revolutionary character was connected to both production and circulation: ideas were articulated and shared collectively and creatively to combat Zionist desubjectification and dehumanisation. Literature became a weapon, or what Kanafani termed ‘the reclamation of the amputated leg’.

The larger Arab world has been essential to the production and dissemination of Palestinian cultural texts, both literature and film. In the face of Zionist ethnic cleansing and the targeting of knowledge-producing institutions, Palestinians turned to the wider region for strategic support. Hawa highlights the importance of Arab publishing houses, which have supported the production of Palestinian resistance literature, including Dar al-Adab and Dar al-Farabi in Beirut, Ittihad al-Kuttab al-‘Arab in Damascus, Dar al-Ahliyyah in Amman, and the General Egyptian Book Organisation in Cairo. Moreover, Arab revolutionary cinema of the 1970s and 1980s, routed through the National Film Organisation of Syria, produced enduring political statements such as Kafr Kassem (1975), filmed in the Syrian village of al-Shaykh Saad, about the 1956 Zionist massacre of Palestinians, and Al-Manam (The Dream, 1987) about the collective memories of Palestinians in exile, filmed in Lebanon’s camps.

The Zionist regime has not only relentlessly attacked sites of Palestinian and Arab cultural production but also destroyed sites of public convocation and collective memory, as witnessed by the looting of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) archives in Beirut in 1982. In Israel’s current carpet-bombing of south Lebanon, the Israeli military has strategically targeted town squares, markets, mosques, and libraries alongside resistance bases, aiming to disperse and isolate Palestinians from communal spaces where culture is exchanged and developed. This attack operates through physical violence and also through institutional destruction.

Love, Revolution, and Life

Wisam Rafeedie embodies the tradition of the militant writer, or an artist who is a member of a political organisation fighting for national liberation. He joined the PFLP at the age of sixteen. After living in hiding for nine years during the First Intifada, Rafeedie was captured by Israeli occupation forces in 1991. Rafeedie received a thirty-four month sentence and was held at al-Naqab prison in the southern Palestinian desert.

There, Rafeedie wrote The Trinity of Fundamentals in 1993, a novel narrated from the perspective of the protagonist Kan’an Subhi, a Palestinian revolutionary and party member who goes into hiding during a period of reconstitution for the resistance in the West Bank. In addition to ‘depicting his struggles through the boredom, despair, and frustration of his isolation, and his maturation into struggle, discipline, and political commitment’, says Hawa, ‘the novel also explores several theatres of tarakum (political accumulation, تَرَاكُم) in this period and is principally about Palestinian revolutionary subjectivity, as co-constitutive with the building of popular institutions and the liberation of the mind’. The trinity of fundamentals that structures Kan’an’s life in hiding is composed of love, revolution, and life itself.

The novel’s circulation embodies the collective practice of Palestinian resistance. The Trinity of Fundamentals spread throughout al-Naqab prison, smuggled in pill capsules and folded into dough balls thrown across prison cells. When a prison guard intercepted the manuscript, Rafeedie believed it was lost. Unbeknownst to him, a fellow prisoner from Gaza had hand-written another version and smuggled it out from al-Naqab to the Nafha prison by swallowing sheets folded into pill capsules. From there, a second copy of the manuscript circulated throughout most of Palestine’s prisons, becoming a staple of the Palestinian Prisoners’ Movement curriculum. The novel documents major moments in the Palestinian struggle, such as the First Intifada and the Gulf War, offering readers a view into internal debates among Palestinian political parties during that period.

Rafeedie’s trajectory mirrors that of other revolutionary cultural workers: Kanafani, who wrote novels while editing the PFLP’s magazine al-Hadaf (The Target) and drafting political programmes; Mahmoud Darwish, who in 1988 wrote the Palestinian Declaration of Independence while serving on the PLO’s executive committee (resigning in 1993 to protest the Oslo Accords); and Kamal Nasser, poet and head of the PLO media department, martyred by Israeli forces in Beirut on 10 April 1973. Hawa notes that these cultural workers and their struggles embody how the intellectual ‘who does not fight for revolution at all times is a false intellectual, and their intellect is deceptive and superficial’, citing Lebanese Marxist theorist Mahdi Amel.

Our People Are Not So Easy to Break

Ilga (Palestine and Chile), Palestina resiste (Palestine Resists), 2016. [Courtesy of Utopix.]

In 2023, several PYM members formed a committee to collectively produce The Trinity of Fundamentals in English. Published in January 2024 by 1804 Books and translated by Dr. Muhammad Tutunji, the new edition brings Rafeedie’s work to audiences beyond the Arab world. ‘Our thinking was that this novel contained within it several forms of knowledge that would be valuable to those coming into political consciousness and beginning their activities in the student and labour movements, or in their local communities’, Hawa explains. ‘Re-reading it now in a moment of brutal, unending sadism and destruction in Gaza, I am struck by just how true it is as a depiction of setback, and how it can help us to continue the fight, to recommit’.

The translation project exemplifies how revolutionary culture functions today. Hawa describes the most important characteristic as ‘the connection between youth culture and the collective experience of Palestinian elders’. After the Oslo Accords vitiated many Palestinian social and cultural institutions through the compradorisation of the Palestine bourgeoisie, Palestinian youth turned to video production and social media diaries to narrate their collective experience, including their alienation and steadfastness. Palestinian elders have struggled against concerted drives from the Arab governments to make them forget their history. ‘We see this connection between generations and geographies as the branches of our fighting spirit as Palestinians, one that needs nurturing by new institutions that are connected to a popular base, mass struggle, and which remain principally unflinching on the subject of Palestinians’ inalienable right to resist Zionism’, Hawa affirms.

A major challenge has been the scholasticide and epistemicide in Gaza – the total destruction of cultural and intellectual repositories in the form of people, institutions, and archives. ‘The heart of Palestine and its revolutionary culture sits in Gaza and the unimaginable loss of that accumulated knowledge and practice is a setback of historical magnitude’, Hawa states. Yet Palestinians remain and resist, writing poetry, song, and testimonies from ground zero of Zionist elimination. The People’s Centre for Palestine, 1804 Books, and Liberated Texts recently completed a translation of Wasim Said’s Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide: A Testimony from Gaza, published by 1804 Books in October 2025. The book weaves together accounts of the atrocities being perpetrated in Gaza, told partly from the author’s home in Beit Hanoun, now levelled. ‘Zionism’s programme of counterinsurgency seeks to destroy the Palestinian spirit – its will to resist and remain, its promise to return – and yet, our people are not so easy to break’, Hawa asserts.

Culture is Life

For Hawa, Palestinian liberation means recognising that, ‘In the Western world, culture is commodity, and the current production and circulation is a culture of death. In a sense, this is unavoidable and we are implicated in it, but I believe that there is value in a collective practice, if only to produce new spaces for the expression of Palestinian culture, which at its core is about life’. For Palestinians, writing is a conduit into universes of thought and experience severed from popular understandings in the West, a connection that is fragile and under siege.

The legacy of Palestinian resistance literature – from Kanafani to Darwish to Rafeedie – calls us to recognise culture as inseparable from political struggle. The Trinity of Fundamentals, written in captivity and smuggled out through collective action, now reaches new audiences through the dedicated work of Palestinian youth. Nearly eight decades after the Nakba, as genocide continues in Gaza, the tradition of militant literature reminds us that cultural work remains essential for Palestinian liberation. As Hawa affirms, the role of the militant writer today is to remain engaged in struggle; to strengthen sumud (صُمُود), or the Palestinian concept of steadfastness and determination to remain on the land; and to resist collaboration with Western Zionist regimes and the normalisation of violence and genocide. The international solidarity built through resistance literature expands the base of popular struggle and keeps the promise of return alive.

In Other News…

Kael Abello (Venezuela), Símbolos de resistencia (Symbols of Resistance), 2024. [Courtesy of Utopix.]

Earlier this month, we published our latest dossier, Despite Everything: Cultural Resistance for a Free Palestine, examining how Palestinian artists have responded to the changing conjuncture since the Nakba through their cultural and political work.

On 30 November 2025, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research alongside the International Peoples’ Assembly and Utopix are organising a webinar to launch the dossier. The webinar will bring together Palestinian novelist Bassem Khandaqji, who was imprisoned by the Israeli regime for nineteen years and recently released in the prisoner exchange, Palestinian actor and filmmaker Mohammad Bakri, and Chilean-Palestinian visual artist Rasan Abu Apara. I will have the honour of moderating the event, which seeks to inspire our continued solidarity work, both cultural and political, until Palestine is free.

Warmly,

Tings Chak

Art Director, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

Across the long arc of Zionist ethnic cleaning, land grabbing, and forced migration, Palestinians have continued to use cultural production as a tool of resistance. Read More