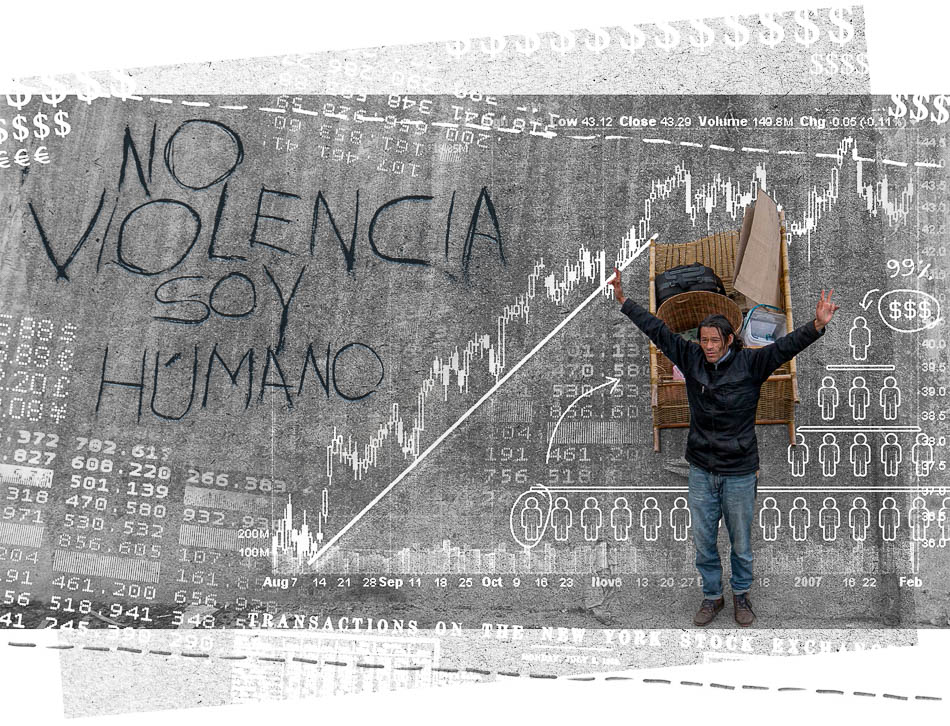

The images in this dossier combine photographs from the Communications Commission of the Popular Unity Process of Southwest Colombia (PUPSOC) with graphic interventions by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. PUPSOC brings together organisations that defend the land and rights of communities across southwest Colombia, a region devastated by the US-led imperialist ‘War on Drugs’ waged in the service of capital. This policy militarises the region, criminalises campesinos, and deepens dispossession, undermining food sovereignty and rural autonomy. Through diagrams, maps, and numbers, the graphic interventions expose how imperialism and capital script this violence while the photographs bear witness to a people who remain in organised resistance, in defence of life, land, and dignity.

Acknowledgments

This dossier is based partly on our Addicted to Imperialism project, for which we have published several texts in Spanish.1

We would also like to thank:

- The National Coordination of Coca, Poppy, and Marijuana Growers (Coordinadora Nacional de Cultivadores y Cultivadoras de Coca, Amapola y Marihuana, COCCAM), who, with their history of struggle and resistance, continue to defend peasants’ rights and build alternatives in the face of the criminalisation of growers of these crops in Colombia.

- The Centre for Political Thought and Dialogue (Centro de Pensamiento y Diálogo Político), who carried out part of the research for our Addicted to Imperialism project and gathered testimonies from the territories that reflect the lived reality of Colombia’s campesinos.

- The Communications Commission of the Popular Unity Process in Colombia’s South-West (Proceso de Unidad Popular del Suroccidente Colombiano, PUPSOC) for the photographic material that accompanies this dossier. Their work, rooted in struggle and organisation alongside communities, has allowed us to illustrate the daily reality of peasant life and resistance with images from their territories.

- The Transnational Institute for its long-standing project of researching and analysing the drug trade since the 1990s, such as bringing to light the suppressed World Health Organisation (WHO) report on cocaine (Transnational Institute, The WHO Cocaine Project, Amsterdam: TNI, 1995). Further reports include Transnational Institute, 10 Years Review: TNI Drugs and Democracy Programme, 1998-2008, Amsterdam: TNI, 2008; Transnational Institute, Global Commission on Drug Policy Report, Amsterdam: TNI, 2011; and Ernestien Jensema, Martin Jelsma, and Tom Blickman, Bouncing Back: Relapse in the Golden Triangle, Amsterdam: TNI, 2014.

Hundreds of years ago, the bandits of early capitalism claimed that they had come to the ‘savage’ lands to bring ‘civilisation’. But what they came to do was plunder: to take land, exploit labour, and extract bullion from across Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Over the generations this banditry became structural, built into plantations, mines, and trading companies that drained that wealth into Europe’s ‘eternal glory’. In time, the bandits’ descendants put on dry-cleaned suits and suggested that the ugliness of the past was not their inheritance, that their fortunes were the product of their diligent entrepreneurship. But beneath them, in the sewers of commercial activity, were the other organised branches of business – the mafia, narcos, arms dealers, smugglers, human traffickers, cyber criminals, loan sharks, animal poachers, organ traffickers, and those who run the scam farms and cybercrime compounds.2 The capitalists above ground and those below are bound together by the circulation of vast, liquid, dirty cash. These illicit funds flow up from below to be cleansed by those above, the smell washed from the money, the notes ironed and creased, then set in motion – for a small discount – as the necessary volume of money that becomes clean capital for licit use.

This dossier seeks to undermine the dominant narrative that presents the ‘War on Drugs’ as a genuine moral crusade by the capitalist states to prohibit the circulation of illicit narcotics. This narrative rests on the claim that the drug trade is somehow separate from ‘legitimate’ capitalism. We argue instead that the War on Drugs is merely an attempt by capitalist states to ensure that these narcotics circuits remain underground so that the money siphoned from illegal trade can continue to liquefy a banking system that would not function without it. Furthermore, beyond laundering criminal profits and waging class war on peasants, the War on Drugs has become a flexible imperial tool for disciplining defiant governments, advancing counterrevolutionary agendas, and opening up territories to capital. While the war is a global regime, this dossier focuses on Colombia’s coca-cocaine economy as a lens through which to examine its political economy.

Our text draws on historical research on the past decades of the War on Drugs, key United Nations (UN) documents, and our own work with campesino (peasant) organisations in Colombia. From their position at the bottom of the commodity chain, campesinos have a clear understanding of the structures that sustain illicit trade. Their organisations have mapped the parallel capitalism that exploits rural producers and their families as well as working-class communities in the wealthier nations, where structural unemployment pushes many into this economy as low-level sellers or consumers.

Photograph (PUPSOC): A participant of the Social and Community Minga for the Defence of Life, Territory, Democracy, and Peace stands next to a wall that reads ‘No violence; I’m human’. As part of the minga (an ancestral, collective work practice that has become a powerful mobilisation tool in the region), thousands marched from Cali to Bogotá, holding massive marches in cities along the way. October, 2020.

Intervention by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

We cannot leave this part of the subject without singling out one flagrant self-contradiction of the Christianity-canting and civilisation-mongering British Government. In its imperial capacity it affects to be a thorough stranger to the contraband opium trade, and even to enter into treaties proscribing it. Yet, in its Indian capacity, it forces the opium cultivation upon Bengal, to the great damage of the productive resources of that country; compels one part of the Indian ryots [peasant cultivators] to engage in the poppy culture; entices another part into the same by dint of money advances; [and] keeps the wholesale manufacture of the deleterious drug a close monopoly in its hands… The chest costing the British Government about 250 rupees is sold at the Calcutta auction mart at a price ranging from 1,210 to 1,600 rupees. But, not yet satisfied with this matter-of-fact complicity, the same government, to this hour, enters into express profit and loss accounts with the merchants and shippers, who embark in the hazardous operation of poisoning an empire.

The Indian finances of the British Government have, in fact, been made to depend not only on the opium trade with China, but on the contraband character of that trade… While openly preaching free trade in poison, it secretly defends the monopoly of its manufacture. Whenever we look closely into the nature of British free trade, monopoly is pretty generally found to lie at the bottom of its ‘freedom’.

Karl Marx, ‘Free Trade and Monopoly’, 25 September 1858.3

Part 1: The Political Economy of Illicit Drugs

From the 1830s onwards, opium grown in India was smuggled into Qing China in ever-larger quantities. Produced under the British East India Company’s opium monopoly in India and sold at auction to private traders, it then moved through smuggling networks along the Chinese coast. In the aftermath of the two Opium Wars fought between Britain and the Qing empire (1839–1842 and 1856–1860, with France joining Britain in the second), the trade was entrenched and its reach widened, flooding the Chinese market with opium.4 This allowed Britain to use the silver it received from opium sales in China to finance its tea purchases, reversing the bullion outflow and turning the China trade profitable. Widespread addiction – including among officials and imperial troops – deepened corruption and weakened the Qing state. Opium’s entry into China made fabulous fortunes for new wealthy families, many of whom are now legendary names in legitimate capitalism such as the Astors, the Forbes, the Delanos (from whom US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt is descended), the Jardines, the Mathesons, and the Sassoons.5 These fortunes also helped establish powerful banks, such as the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Company (HSBC), founded in 1865. Opium profits contributed to the capital accumulated to build the infrastructure of the imperial centres, including the railroads in the United States, built in the mid to late nineteenth century and heavily reliant on Chinese migrant labour. Capital accumulated in the China trade also flowed into US enterprises through investments by major Chinese merchants such as Wu Bingjian (Houqua).6

By the late nineteenth century, the consequences of highly profitable and readily available opium were no longer confined to China. The drug had made its way into the imperial centres, with addiction rates rising in the North Atlantic states. Social reformers in these parts of the world intensified campaigns to prohibit the entry of opium, but all they were able to do was to drive the entire industry into the arms of increasingly powerful criminal organisations. The period of US alcohol prohibition between 1920 and 1933 marked a profound shift in the political economy of drugs. The ban on alcohol – alongside tightening controls on narcotics – fuelled the exponential growth of the illicit economy, equipping criminal organisations with unprecedented resources and influence. Local gangs transformed into national syndicates, extending their reach into political institutions. When alcohol prohibition was repealed in 1933, heroin and other narcotics remained the central source of income for this burgeoning criminal infrastructure and an important source of liquidity for the legal banking structure. The profits from illegal enterprise, vast as they were, became the source of a steady infusion of cash into the legal economy.

Colonial plunder of coin, land, and labour, alongside the enclosure of the commons in England between 1750 and 1860, formed the basis for what Marx called ursprüngliche Akkumulation, or ‘originary’ accumulation, in Capital, volume 1. There was no anxiety about legality. The entire process of accumulation was bathed in blood – the conquest of vast territories, the capture of entire peoples, and the trade in anything that could be bought and sold, including the deadliest drugs and human beings. That is how capitalism was born, certainly, but that is also how capitalism survives. Originary accumulation is not a one-off prelude that sets in place a perpetual motion machine. It can be understood as periodic: originary accumulation resumes once more whenever capital, starved of liquidity, seeks out new reservoirs to satisfy its need – much as a vampire seeks fresh blood for its sustenance.

The economy of illicit commodities – whether the traffic of drugs or people – has a peculiar logic that differentiates it from the economy of legal commodities. Once a commodity is designated by the state as illegal, it exits the entire apparatus of regulation. Those who work to produce the commodity, from its primary stage (the campesinos who grow the coca leaf, for instance) to its final stage (the drug dealers who sell cocaine in its various forms), are without any legal protection and are therefore vulnerable to super exploitation at unimaginable levels.7 The primary products are priced so far below their street value that they generate enormous amounts of cash for those who control the pipeline from purchase at the source to sale on the street. The production chain for cocaine is illustrated below:8

- Coca leaf cultivation

-

- Process: The coca leaf is grown mainly in the Andean region (Bolivia, Colombia, and Peru). The leaf is harvested several times a year by raspachines (hired coca leaf pickers) and sold at the ‘farm gate’ (directly from the producer, before transport or processing) to intermediaries. A share of the coca leaf is used legally (for traditional chewing, or mambeo, and for tea). The remainder goes into illicit processing toward cocaine.

- Prices: In Colombia, which has been the world’s largest coca cultivator in recent years, the farm-gate price of coca leaf has collapsed in many regions. A recent report shows that between 2022 and 2023, the price of an arroba (a 12.5-kilogramme bushel) fell from $20 to $7 in Nariño and from $17 to $9 in Argelia (Cauca).9

- Purpose: Campesinos sell at the bottom of a chain they do not control; illegality strips protections and creates a buyer’s market at the farm gate.

- Pasta básica (coca paste) processing

-

- Process: In small, clandestine labs, workers macerate the coca leaf by hand, using petroleum distillates to extract the alkaloids from the leaf. This material is then dried to produce coca paste.

- Prices: Coca paste prices vary across the region, but one indicative figure is that in Colombia a kilogramme of coca paste could be sold at the lab gate for between $450 and $600 over the past five years.

- Purpose: Intermediaries turn leaf into a concentrate, and with concentration comes the first big markup – value that does not return to the farmers.

- Coca paste to cocaine hydrochloride (cocaine powder)

-

- Process: Some processes use mineral acids to change the chemical form of the extracted alkaloids. Workers then use alkaline substances to change the solubility of the alkaloids during processing. Further steps may involve oxidising agents or solvents to purify the product. These chemicals – often easily available due to their use in agriculture and industry – are handled and mixed by workers using extremely unsafe methods, including bare hands and sticks.

- Prices: At the gate of this processing site, the price rises to over $1,000 per kilogramme, although today it can reach several thousand dollars depending on the quality of the cocaine hydrochloride.

- Purpose: Refining standardises the drug for wholesale markets, converting it into a high-value commodity that can move like money.

- Wholesale and retail trafficking

-

- Process: The cocaine powder is then transported from the Andean countries to transit hubs – especially in Central America, the Caribbean, Brazil, and West Africa – by armed groups and criminal organisations. The high-purity product is sold in bulk between trafficking organisations.10 Traffickers then carry the drug to consumer countries (mainly the US and Western Europe) where the product is cut, repackaged, and distributed to small wholesalers (mainly gangs) before reaching the streets through retail dealers.

- Prices: Recent data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) about prices over the past decade in Mexico suggests that the transit price is roughly $12,000 per kilogramme. In Panama, the price has been recorded at $30,000 per kilogramme. The retail price in Kenya varies widely, with one estimate putting it at $90 per gramme at around 56% purity and a wholesale price of $44,580 per kilogramme at between 40% and 50% purity.11

- Purpose: Wholesale and retail sales generate the bulk of profits in cash, which is then laundered and reinvested, supplying liquidity to the formal economy.

Taken together, the above figures show how value rises by orders of magnitude from farm-gate coca leaf in Colombia, priced at between $0.56 and $0.72 per kilogramme, to wholesale cocaine in Kenya, for example, at $44,580 per kilogramme – a price increase of roughly 62,000–80,000 times (about 6.2 to 8.0 million per cent).

The nature of illicit commodities like cocaine is such that demand is largely price-inelastic (meaning that consumption changes little even when prices rise), especially among dependent users, since addiction keeps users coming back regardless of price. In some cases, price increases push users towards petty theft or other informal income to meet those costs. The violence in the passage of the drug from farms to the streets, and the violence of overdoses, rarely disrupts either production or the market, since unemployment and precarity ensure a reserve army of labour that can be pulled into the trade when others are killed, incarcerated, or forced out. In this way, lives can be expended without disrupting the process of capital accumulation in the formal economy. Deindustrialised towns with high unemployment rates conveniently provide a pool of recruits and consumers for a drug economy that both employs sections of the population, addicts many, and then allows for coercive repression by state forces in the name of the War on Drugs.12 The economy of illicit commodities, therefore, super-exploits workers, produces enormous volumes of cash that are laundered into – and thereby lubricate – the financial system, and allows marginalised communities to be controlled through social demoralisation and police intervention.

The link between narcotics and capitalism is not confined to the underworld: the same plants and molecules that travel through illicit circuits also supply perfectly legal industries. Opium poppies feed the global pharmaceutical market with painkillers and sedatives. Coca leaves are processed into decocainised flavourings and medical products. Synthetic opioids such as fentanyl are manufactured under licence by major drug companies. In each case, states design regulatory and trade regimes that protect corporate profits while criminalising parallel informal circuits. The frontier between ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ drugs is therefore not chemical but political, drawn in ways that favour capital accumulation in the imperial centres and expose peasants and poor consumers in the peripheries to criminalisation and violence.

The vast volumes of liquid money flowing through the hands of criminal cartels and laundered into banks offer an enormous temptation for governments to use that money for off-the-books covert operations. In practice, this often takes the form of covert alliances with proxy forces – including protection, training, arms, and logistics – operating inside narcotics economies and financing themselves by taxing cultivation, processing, and transit. In this way, illicit revenue can subsidise proxy warfare while insulating the sponsor government from public oversight. These are the kinds of circuits used by the United States to fund counterrevolutionary forces against left or communist movements in the decades after the Second World War. Examples include Kuomintang (KMT) remnants in Burma and northern Thailand (early 1950s–1960s), mobilised against the People’s Republic of China and communist forces along the border in northern Myanmar and Thailand; the Hmong Secret Army under General Vang Pao in Laos (c. 1960–1973), mobilised against the Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese forces; the South Vietnamese armed forces (1955–1975), mobilised against the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) and North Vietnam; the Afghan mujahideen (late 1970s–1980s), mobilised against Afghanistan’s Soviet-backed PDPA government and, after the Soviet intervention, against Soviet forces; the Nicaraguan Contras (1980s), mobilised against the Sandinista government; and Colombian paramilitaries, notably the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, AUC, 1997–2006), mobilised against the FARC-EP13and the wider left.14 A security state that treats the world of illegal drugs as a bank for its own covert operations has little incentive to dismantle these circuits. There is ample evidence of the cartels themselves using their contacts within the security services to take out rivals so that they can grow their own operations into new territory. The symbiotic relationship between illegal gangs and the para-legal covert agencies of the state is well-documented.15

The paradigm of the War on Drugs has allowed the United States, the principal architect of this campaign, to depict any of its adversaries as narco-traffickers and use its immense military and financial might against them. The basis of Plan Colombia (launched in 2000 as a US-Colombian initiative) was to use counternarcotics funding to arm the Colombian military, whose main focus of attention was not the narco-traffickers, who had infiltrated the state and security apparatus, nor the right-wing paramilitaries, which worked closely with the narco-traffickers, but revolutionary groups such as the FARC-EP and the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN).16 In practice, Plan Colombia’s counternarcotics architecture also operated as a counterinsurgency and territorial-recapture project aimed at reasserting state control in coca-growing regions (the FARC-EP itself emerged from campesino self-defence communities and drew much of its social base from rural Colombia). More recently, the rhetoric of the War on Drugs has been used to escalate pressure on countries across the region whose governments refuse to be supine before the United States (mainly Venezuela, Colombia, and Mexico). In August 2025, Washington began to escalate this framing against Venezuela by designating the alleged Cartel de los Soles (Cartel of the Suns) as a ‘transnational terrorist group’ with supposed ties to President Nicolás Maduro. Despite offering zero evidence for the connection (or even of the existence of this ‘cartel’), the US has engaged in a violent campaign against the Bolivarian Revolution that includes, most recently, extrajudicial strikes on small boats in the Caribbean (killing more than one hundred people by the end of 2025), a naval blockade of sanctioned Venezuelan oil tankers, and the 3 January 2026 bombing of Caracas and kidnapping of President Maduro and National Assembly Deputy Cilia Flores, who are being tried in a New York court on unfounded charges including and related to ‘narco-terrorism’.17 (It is worth noting that, within days of the kidnapping of Maduro and Flores, the Department of Justice dropped ‘the claim that Venezuela’s “Cartel de los Soles” is an actual group’, as one The New York Times article put it).18

This narrative relies on an information war predicated on exaggeration, misdirection, and outright lies. According to the US’s own Drug Enforcement Administration, Colombia remains the principal site of coca cultivation and the main source country for cocaine seized in the United States. Moreover, most cocaine bound for the North American market departs Colombia via the Pacific and moves through Central America and Mexico, with Venezuela accounting for only 5% of drugs transported through Colombia.19 Though Venezuela is responsible for a negligible amount of the global drug trade, it nonetheless remains at this time a main target of the US war on drugs. This is not only a blatant disregard of the facts, but also a violation of international law and a clear example of how the War on Drugs narrative is used to discipline left forces in the region and drain wealth from South to North.

Photograph (PUPSOC): A child participates in a 2020 tribute in Popayán, Cauca, honouring protestors who were injured and killed by police repression during the 2019 social uprising – many of them left permanently blind.

Intervention by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

According to one estimate, in 2015 the unequal exchange of goods and services between the Global North and the Global South totalled $10.8–$14.1 trillion (enough to end extreme poverty 70 times over).20 This is a vast number that has not been fully digested by those who shape policy. It means that every year, over $10 trillion of wealth is drained from the South to the North, mostly legally. The illicit capital flight is not as high, although the five top areas of illegality are stunning, even with conservative estimates: the illegal trade in small arms ($3.5 billion), the drug trade ($32 billion), illegal mining ($48 billion), human trafficking ($150 billion), and counterfeiting ($467 billion) together amount to about $700.5 billion per year21 What is notable about illegal trade is that it produces enormous volumes of cash. In 2011, the UNODC published an important report on the illicit financial flows from drug money.22 The key findings are worth reflecting upon, since there is no updated global data on these issues:

- A large share – up to 70% – of the proceeds from transnational organised crime is estimated (with high uncertainty) to be laundered through the financial system.

- The report’s best estimate of the total illicit proceeds that are available for laundering is 2.7% of global GDP, or $1.6 trillion in 2009.

- The illicit drug trade is estimated to be the largest transnational organised crime market, accounting for about 20% of all proceeds of international crime.

- The interception rate is strikingly low: only about 1% (likely around 0.2%) of drug proceeds are seized or frozen.

A newer UNODC report from 2023 argues that in several countries, illicit financial flows (IFFs) related to drug money are comparable to – and in some cases larger than – legal cross-border flows.23 In Colombia, for example, the report estimates (through modelling) that annual inward IFFs related to cocaine trafficking were between $1.2 and $8.6 billion from 2015 to 2019. By comparison, according to preliminary government reporting, Colombia’s foreign direct investment inflows in 2024 were about $14.2 billion.24 In Mexico, inward IFFs related to trafficking in heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine totalled between $8 billion and $17 billion per year from 2015 to 2018, roughly comparable to its average agricultural export earnings over the same period ($12.6 billion). These figures should be read as indicative, since most countries do not collect reliable national statistics on IFFs.

Money-laundering networks and financial intermediaries use a variety of means to move cash and value. Among them are informal cash-transfer systems (such as hawala and hundi)25, cryptoassets and digital services, and the exploitation of migration and remittance channels to move cash outside the regulatory eye of the state. Though the UN has produced a new methodology to measure illicit finances, it does not compensate for the shadowy world of the black market.26 For that reason, the 2011 UNODC report noted, ‘the final monetary estimates are to be treated with caution’.27

Occasionally, there is a scandal over the involvement of a bank in laundering drug proceeds. The most prominent such case involved HSBC, which grew out of the opium trade to become one of the world’s largest banks, with more than $3 trillion in total assets as of 2025.28 In 2012, a US Department of Justice investigation found that HSBC had laundered about $881 million for Colombian and Mexican drug cartels between roughly 1996 and 2006. The bank agreed to pay $1.9 billion in penalties under a deferred prosecution agreement, but it was not shut down and no HSBC executives were criminally prosecuted as part of the settlement.29 Since only a small share of these crimes is ever detected, one can assume that the fine was modest relative to the profits.

Smaller banks, meanwhile, have been shuttered when similar investigations (however rare) have been carried out. In October 2015, Banco Continental in Honduras was forced into liquidation after the US Office of Foreign Assets Control designated the bank as a ‘specially designated narcotics trafficker’ (the amount allegedly laundered was never disclosed). Such actions ostensibly amount to show trials to display the wrath of regulatory bodies that are otherwise lenient when the target is a US or transnational bank. The system cannot be touched, and there can be no reform of the entire rotten banking system (including illicit tax shelters that house trillions of dollars). The global Financial Action Task Force, established in 1989 by the G7, is supposed to provide a framework against money laundering.30 But, as a recent study notes, its failure ‘to reduce either the predicate crimes that generate large criminal revenues or the volume of money laundering is uncontested’.31 Each year, UN estimates suggest that both the sums laundered and the illegal activity that generates them continue to rise.32

Whether the narcotic drug is plant-based (cocaine) or synthetic (methamphetamine), its production is pushed into rural and peripheral areas where people live in poverty or near poverty. The drug is then transported by cartels over vast distances to consumer markets, where impoverished youth sell it for wages that exceed what they could earn in the uberised, precarious economy yet remain modest compared to the value they move. The cartel bosses, meanwhile, draw vast amounts of wealth from the trade, but their lives are often short and violent. The formal banking system, which receives volumes of cash that are siphoned out of the commodity chain, ends up profiting handsomely while remaining largely insulated from consequence. In the long run, the risks – violence, imprisonment, dispossession – are concentrated among campesinos and the urban poor, while the surplus is absorbed and reinvested through the institutions of ‘legitimate’ capitalism.

Photograph (PUPSOC): Members of the Estrella Roja (Red Star) Ecovillage and the Humedal La Orquídea (Orchid Wetland) Environmental Committee participate in a reforestation project in the Cauca River basin.

Intervention by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

My country is beautiful because it has the Amazon rainforest, the Chocó rainforest, the waters, the Andes mountain range, and the oceans. There, in those rainforests, planetary oxygen is released, and atmospheric CO2 is absorbed. One of those plants that absorbs CO2, among millions of species, is one of the most persecuted on Earth. Wherever it grows, its destruction is sought. It is an Amazonian plant. It is the coca plant, the sacred plant of the Incas.

As if at a paradoxical crossroads, the jungle that we are trying to save is, at the same time, being destroyed.

To destroy the coca plant, you spray poisons, massive amounts of glyphosate that run through the waters, [and] you arrest its growers and imprison them. To destroy or possess the coca leaf, a million Latin Americans are murdered and two million African Americans are imprisoned in North America.

‘Destroy the plant that kills’, you shout from the North; ‘destroy it’. But the plant is just one more plant [among] the millions of species that perish when you unleash fire on the rainforest.

‘Destroy the Rainforest’, ‘[destroy] the Amazon’ have become the slogans followed by states and businessmen. The cry of scientists baptising the rainforest as one of the great climate pillars does not matter. For the power brokers of the world, the rainforest and its inhabitants are to blame for the plague that torments them. The power brokers are plagued by the addiction to money, to self-perpetuation, to oil, to cocaine, and to the hardest drugs so they can anaesthetise themselves even more.

Nothing is more hypocritical than the discourse about saving the rainforest. The rainforest is burning, distinguished delegates, while you wage war and play with it. The rainforest, the climate pillar of the world, disappears with all its life. The enormous sponge that absorbs the planetary CO2 evaporates. The rainforest – our saviour – is seen in my country as the enemy to defeat, as weeds to be eradicated.

The space of coca and of the peasants who cultivate it, because they have nothing else to cultivate, is demonised. My country does not interest you except to fill its rainforests with poison, to take its men to prison, and to cast its women into exclusion.

You are not interested in educating children but rather in killing the rainforest and extracting the coal and oil from its entrails. The sponge that absorbs the poison is useless; you prefer to spread more poison into the atmosphere.

We serve to excuse the emptiness and loneliness of your own society that lead you to live in your bubble of drugs. We conceal from you your own problems that you refuse to reform. It is better to declare war on the rainforest, its plants, its people.

Gustavo Petro, president of Colombia, address to the UN General Assembly (General Debate, 77th session), 20 September 2022.33

Part 2: How the Campesinos See the ‘War on Drugs’

Petro’s indictment names what half a century of drug policy has tried to obscure: that this ‘war’ has been waged not against narcotics, but against people and nature. The modern architecture of this ‘war’ dates back to 17 June 1971, when US President Richard Nixon told reporters that ‘public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse’.34 ‘In order to fight and defeat this enemy’, he continued, ‘it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive’. The announcement prompted the US media to coin the term ‘War on Drugs’. Initially, Nixon said that the target of the war would be the ‘pusher’, or the drug dealer. There was little care in the language of ‘war’ to tackle the drug addiction generated by the US war in Vietnam – a war that helped produce the very crisis that the War on Drugs purposed to confront. Rather than focus on addiction and on the industry that preys on the addict, the United States very soon used the War on Drugs to go after not only the poor within its own borders, but also impoverished peasants in Latin America and Asia left with no choice but to produce drugs, conditions that the US itself had contributed created. There was to be no real war against addiction or the system that produces it – only a war against the peasantry and against the revolutionary organisations that worked among them.

The legal instrument that Europe and the US needed in order to wage this war was already available: the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.35 Presented as an international public health framework, it placed plants such as coca, cannabis, and poppy under international control and obliged states to limit their production and use to medical and scientific purposes. The convention also required the abolition of coca leaf chewing after a ‘transitional’ period, in effect criminalising a millenarian indigenous practice in the name of global ‘order’. This was not a neutral classification: it was a political decision taken in an international system dominated by the North that turned certain plants – and the people whose lives and cultures are entwined with them – into objects to control.

The Colombian case is paradigmatic for understanding the concrete effects of the long-standing War on Drugs, precisely because it makes visible the links between crops, rural underdevelopment, and armed conflict – a policy framework that today is being reissued and recycled once again. As we discussed in notebook no. 1 of our Addicted to Imperialism research project, ‘coca leaf production in Colombia has some unique characteristics that relate to the connection between crops, lack of rural development, and armed conflict’.36 Far from what the media would have us believe, and far from being the result of a ‘criminal association’ between large drug cartels and peasant communities, Colombia’s coca economy is rooted in the country’s historical development and the evolution of its armed conflict. That conflict – involving state forces, left guerrilla insurgencies (including the FARC-EP and the ELN), and right-wing paramilitaries – has deep roots in land inequality and political exclusion, in which the United States has, unsurprisingly, played a leading role.

Despite its early importance as a major entrepôt for colonial trade and as the seat of the Spanish empire’s viceroyalty of New Granada, for much of its history Colombia remained a largely rural country with an agrarian economy. From the nineteenth to early twentieth century, tobacco, sugarcane, bananas, and coffee exports made the country profitable, but so too did the extraction of gold and emeralds. Though the balance of trade has shifted, Colombia remains an exporter of agricultural commodities (such as coffee, avocado, palm oil, alongside coca and cocaine) and energy (chiefly oil and coal). This export-extractive order rests on land concentration and coercive force, producing recurrent rural conflict. The intense class struggle in the countryside has been re-enacted generation after generation, from the Masacre de las bananeras (Banana Massacre), when United Fruit Company henchmen opened fire on striking workers and their supporters in Ciénaga in December 1928 (killing an estimated 1,000), to the Mapiripán massacre of 1997 in Meta, when AUC paramilitaries murdered and ‘disappeared’ approximately 49 civilians in a counterinsurgent campaign to seize territory and secure drug trafficking routes.37

In recent years, the violence has largely been over the development of new forms of capital investment and commodity extraction in the countryside. Parastatal armies are mobilised to expropriate large tracts of land for livestock production, for large-scale monoculture of sorghum, soybeans, wheat, palm, cotton, maize, and rice, and for purely extractive mining and agro-industrial projects tied to domestic elites and transnational capital. The very existence of the peasantry poses a problem for these operations. Peasants are directly attacked through the process of violent dispossession, but also through the structural conditions imposed upon them: the deflation of prices for small-holder crops (driven by trade liberalisation, buyer power, and the absence of price supports) and the attrition of social welfare systems – both of which deepen poverty.38 Where this dispossession succeeds, peasants gather in the peripheries of urban areas, or else become fodder for the vast trafficking networks of drugs and other illegal commodities controlled by the very groups that drive them from the land. These criminal organisations establish new rural and urban dynamics of territorial control while at the same time providing precarious economic opportunities for rural workers.39

Photograph (PUPSOC): A campesino anfibio (‘amphibious’ campesino – meaning working on land, in rivers, and at sea), fishes in Santa Marta, Colombia, on the Atlantic Coast.

Intervention by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

What is apparent in Colombia is also happening across Latin America: the deepening of the neoliberal model in agriculture has hastened the extinction of the small-holder farmer. Peasants face a lack of access to and tenure of land as well as social and economic exclusion, unemployment, oppression, and marginalisation, which is further compounded by weak public policy, inadequate rural health and education, and the inability to access decent housing. In Colombia, the crisis is further intensified by land grabbing, usurpation, and legalisation – the ‘regularisation’ of illegally dispossessed land – carried out through a paramilitary model with state financing and consent in the service of large transnational corporations. Land concentration is extreme: large landowners control the overwhelming share of productive land, with the largest 1% of landholdings (farms larger than 100 hectares) accounting for 81% of agricultural land.40

Taken together, these dynamics reproduce a long history of dispossession that stretches back to the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the Americas. In Colombia, sections of the state apparatus collude with drug traffickers and paramilitary groups to violently take the peasants’ land and strip them of the means to reproduce themselves. At the same time, free trade agreements and import competition undercut licit crops, pushing farmers towards more profitable illicit crops. Although coca is native to the Andes and has deep spiritual and cultural significance for indigenous peoples who have used it for thousands of years, most farmers are now forced to grow coca under the same neoliberal system that then turns around and tries to eradicate the crop in the name of the War on Drugs.

Coca production locks households into economic dependence and highly informal work throughout the year, since the mature coca leaf is harvested every two months. In addition, it achieves rapid production at low cost, prompt commercialisation, and an average net monthly income estimated at about 56% of the Colombian minimum wage (in 2018) per hectare cultivated.41 However, this figure masks wide variation and does not reflect how coercion, intermediaries, transport bottlenecks, and price volatility can further squeeze what growers take home. Our joint research with the National Coordination of Coca, Poppy, and Marijuana Growers (COCCAM) found that not only is production labour intensive and time consuming, but the rate of return for peasants is negligible. According to one COCCAM leader:

When we finish the whole process, we are practically ready to start again. So, it is constant… The coca is planted, and after six months it is ready for the first harvest, and then it is harvested every two months, which means that every two months there is a product.

Another COCCAM member, a 26-year-old grower, said:

You may need between six and ten workers per hectare. That needs to be emphasised, because coca leaf generates a lot of employment. There are farms where the picking never stops and there are 60 to 80 workers every day. That means that during the course of the year, they will rest for one month.42

Furthermore, coca-growing areas are among the poorest and most isolated in Colombia, with markedly lower access to public goods and services than the rest of the country. A 2018 UNODC household survey of 6,350 families in 29 municipalities participating in Colombia’s Integral National Programme for Illicit Crop Substitution (Programa Nacional Integral de Sustitución de Cultivos Ilícitos) found that 57% of households were in monetary poverty and 47% were multidimensionally poor.43 UNODC calculates its multidimensional poverty index across four dimensions – education, health, childhood and adolescence, and housing conditions – and classifies a household as multidimensionally poor when it is deprived in at least one-third of the weighted indicators. The same survey points to pervasive child labour (92% of children aged 6–9 are working), low school attendance (68% of the school-age population does not attend), and severe service deficits (only 3% report access to a hospital or health centre, while only 63% report access to electricity).44 The health effects associated with tasks performed in growing illicit crops go beyond those associated with agricultural work. Added to this are the damages caused by the products used to treat the plantations and by the institutional measures for eradication (such as the indiscriminate spraying of glyphosate over peasant territories), as well as the impacts of deforestation to expand the agricultural frontier. Across these territories, labour informality is near universal and overcrowding is widespread. In addition, birth rates are high, and adult migration is common – dynamics that crop substitution and alternative development programmes rarely take into account.45 These are conditions of state abandonment that both sustain and are reinforced by the coca economy and the coercive structures around it.

These conditions are central to understanding why peasants sell their labour in the illicit coca economy – it is one of the few viable sources of cash income. As one COCCAM leader put it:

The peasantry has been judged and labelled as if we chose to cultivate the coca leaf, when it has been the circumstances, the lack of involvement of local and national governments in the territory… The absence of this institutionality has led people to seek alternatives with illegal economies to feed, maintain, and sustain [their] families. This is due to the lack of good access roads, produce markets [and collection centres], and initiatives to promote production.46

Although illicit activities surrounding the coca leaf began decades earlier, Colombia’s emergence as a central node in the global cocaine trade took shape in the 1970s, when rising international demand drew the country into large-scale processing and export.47 By the end of the decade, Colombia was one of the world’s main exporters of cocaine and marijuana, generating an influx of capital that reshaped the country’s economy and politics – a transformation that continues today. In the 1980s, cocaine trafficking consolidated at the expense of other drugs and cultivation expanded into more regions of the country, even as it declined in Peru and Bolivia. This trajectory accelerated in the 1990s: between 1995 and 2000, the area under coca cultivation in Colombia rose from about 50,900 hectares to 136,200 hectares, representing roughly 0.1 to 0.3 per cent of the country’s agricultural land.48

Between 1994 and 2005, the expansion of coca production intensified internal conflict, led to the expansion of the agricultural frontier, altered population growth patterns, and deepened inequality. It also drove cultural changes linked to shifting rural-urban relations, internal migration, and changes in crop planting and production. Across this period, minors were increasingly drawn into the armed conflict between insurgent groups and the Colombian state’s legal and illegal armies through recruitment and coercion by armed actors, including as combatants and in support roles. Coca expansion also reshaped settlement patterns, drawing internal migrants (including displaced families) into frontier zones and swelling existing town centres into hubs of trade and services.49

During the 1980s and 1990s, large drug cartels emerged in Medellín and Cali, building vast empires of wealth and territorial power. Although these empires were based in these departmental capitals, the business of production and processing took place in other parts of the country, particularly in the south, southwest, and in the east and northeast. In practice, the persecution of the cartels by the Colombian and US governments turned into a witch hunt to criminalise peasant farmers and the armed political organisations that are present in these regions of the country, providing an ideal backdrop for the development of Plan Colombia. This plan led to an intensification of political violence in the country, with direct US financing for the War on Drugs, which ultimately resulted in increased militarisation and paved the way for a succession of right-wing presidents who instrumentalised the War on Drugs to deepen their grip on society: Álvaro Uribe Vélez (2002–2010), Juan Manuel Santos (2010–2018), and Iván Duque Márquez (2018–2022).

Colombia’s coca economy has become entrenched in regions where the state’s presence has long been militarised while civilian institutions and public services have remained weak. In these territories, conflict over land is sharpened by insecure tenure and overlapping claims, and armed actors – legal and illegal – who extract resources from peasant households and whose livelihoods depend on coca as a cash crop. As one COCCAM regional leader explained:

Currently, there are no guarantees for those involved in cultivating coca leaves. Over the years, [land] concentration has become more critical in the regions… In addition, illegal and legal armed actors take advantage of the situation of the peasantry: more than one has demanded resources, which the peasant agrees to hand over to prevent the uprooting of the plant… their only means of subsistence.50

Yet these same conditions have fuelled generations of organised struggle. The peasantry in Colombia has a long tradition of political organisation around peasant rights, land, production, and the defence of territory. It is no coincidence that peasants have historically stood at the forefront of struggles against the expansion of latifundios (large, privately-owned agricultural estates) and the predatory practices of national and foreign capital, from the creation of guerrilla organisations in the 1960s to more recent forms of organising around agricultural labour. These struggles have repeatedly moved from the countryside to the streets and highways, despite police repression, criminalisation, murder, and state abandonment.

The peasant movement in Colombia has also built tools for organising in coca-growing territories. Notable here are the peasant marches of 1994 during the government of Ernesto Samper Pizano (1994–1998), led by coca growers in the departments of Caquetá, Putumayo, and Guaviare against the government’s glyphosate spraying policies. When the state failed to honour the resulting agreements, peasants, raspachines, harvesters, merchants, settled farmers, and day labourers launched a new wave of mobilisations in 1996, which became a defining feature of the decade’s social struggles.

The San Vicente del Caguán peace talks (1998–2002) – negotiations between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP – placed coca-growing territories at the centre of national debate, not only as sites of drug trafficking and armed conflict but also as places where large civilian populations depended on the coca economy for survival. In territories such as Guaviare, Putumayo, Caquetá, Meta, Catatumbo, and Cauca, this economy sustained a population of around one million growers, raspachines, collectors, cooks, and others who survive amid constant dispute between armed actors and precarious living conditions. These communities were not new, but they were increasingly treated as a distinct political subject – the coca-growing peasantry – shaped in part by internal migration into frontier agricultural zones. Because coca cultivation was treated as an enemy economy, these communities faced intensifying repression as the armed conflict between the FARC-EP and the Colombian government escalated, alongside territorial disputes and the co-opting of political power by drug traffickers. To make matters worse, the state has long approached this as a question of public order – eradication and militarisation – rather than public policies such as guaranteeing land rights, rural investment, and peasants’ livelihoods.

With the signing of the Final Peace Agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP in 2016, the state formally recognised the need for a definitive and comprehensive solution to the problem of illicit drugs – one that treats the peasantry as subjects of rights and advances public policy through differential approaches. In early 2017, COCCAM was established, bringing together peasant, indigenous, and Afro-descendant communities from across Colombia to discuss the situation of growers and harvesters and to demand participation in eradication and substitution.51

Mass demonstrations in 2019, including the national strike in November, helped consolidate a broad popular bloc that later coalesced into the Pacto Histórico (Historic Pact) electoral coalition, bringing together forces such as Colombia Humana (Humane Colombia) and Unión Patriótica (Patriotic Union), among others. This bloc broke the back of the right-wing consensus and carried Gustavo Franscisco Petro Urrego to the presidency in 2022.

Petro has argued that the US-led War on Drugs has failed and has called for shifting policy away from the criminalisation of coca-growing peasants and towards the entire structure of the illicit economy. This shift marks the beginning of a rupture. A deeper break would require an assault on the entire banking system, which is fuelled by the originary accumulation from the illicit economy – a confrontation that would reach into the heart of capitalism itself.

Conclusion

Over the past several years, our work with peasant organisations across the world – particularly COCCAM in Colombia – has allowed us to examine the drug economy not as a matter of crime and security but as a window into the deeper structures of contemporary capitalism. Campesinos know that the illicit coca economy is not the cause of Colombia’s crisis but one of its symptoms. These farmers enter the illicit economy not out of choice but because all other avenues of dignified subsistence have been blocked by land dispossession, collapsing agricultural prices, the retreat of the state, and the expansion of paramilitary and corporate power.

From the standpoint of these communities, the dominant narrative of the War on Drugs is revealed as a profound misdiagnosis. The problem is not the coca plant but the economic system that criminalises the rural poor while absorbing and recycling the enormous liquidity generated by illicit markets. The financial sector depends on these flows. Global banks welcome them. And the wealthier nations that promote eradication simultaneously rely on the stability that this hidden capital provides. To treat the campesino as the enemy is to conceal the real architecture of the drug trade, which stretches upward into the circuits of legal finance, global commodities, and state power.

If the objective is to end the violence and the economic dependence on coca cultivation, then the starting point must be neither militarisation nor eradication but the reconstruction of rural life: land reform, guaranteed prices for licit crops, infrastructure, public services, and political rights for those who cultivate the soil. Without transforming the social and economic conditions that push families into illicit agriculture, the cycle will simply reproduce itself. Without confronting the financial institutions that launder the proceeds, the global drug economy will continue to function as an unofficial pillar of capitalist liquidity.

This is not a text that intervenes into public policy from the standpoint of security or drug addiction. Our starting point is the well-being of the millions of workers who are pushed into growing coca, processing it into cocaine, and transporting and selling the product. None of these workers benefit from the billions of dollars that swirl around the drug trade and liquefy the international banking system. Treating the drug trade as outside the licit economy is an enormous category error, since it obscures the function of the drug money inside the capitalist system itself. Eradication, criminalisation, and militarisation will not end the production of coca or the illicit economy.

The peasantry knows this truth intimately. Their experience shows that the drug economy persists not because of the coca leaf itself, but because capitalism requires the constant replenishment of new reservoirs of wealth – licit or illicit – to sustain itself. Any genuine solution must therefore begin with the campesinos and with the recognition that the frontier between legal and illegal capitalism is far thinner, and far more politically useful, than the architects of the War on Drugs will admit.

Photograph (PUPSOC): Campesinos travel to Monterredondo (Miranda, Cauca) to welcome former FARC combatants at a Territorial Space for Training and Reincorporation (ETCR) following the 2016 peace agreement.

Intervention by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

Notes

1See Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Adictos al Imperialismo, https://thetricontinental.org/es/argentina/investigaciones/adictos-al-imperialismo/.

2Andrew Feinstein, The Shadow World: Inside the Global Arms Trade (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011); Moisés Naím, Illicit: How Smugglers, Traffickers, and Copycats Are Hijacking the Global Economy (New York: Knopf, 2006); María José Ramos, El tráfico ilegal de fauna en América Latina [Illegal wildlife trafficking in Latin America] (Buenos Aires: Mágicas Naranjas, 2018); Roger Botte, Esclavages et traite des êtres humains au Sahel [Slavery and Human Trafficking in the Sahel] (Paris: Karthala, 2000); and Ivan Franceschini, Ling Li, and Mark Bo, Scam: Inside Southeast Asia’s Cybercrime Compounds (London: Verso, 2025).

3Karl Marx, ‘Free Trade and Monopoly’, New York Daily Tribune, 25 September 1858.

4The definitive history in Chinese is by Haijian Mao, Tianchao de Bengkui: Yapian Zhanzheng Zai Yanjiu [The Qing Empire and the Opium War: The Collapse of the Heavenly Dynasty], (Beijing: Shenghuo·Dushu·Xinzhi Sanlian Shudian, 2005), and an excellent English synthesis is by Julia Lovell, The Opium War. Drugs, Dreams, and the Making of China, (Oxford: Picador, 2011).

5Jacques M. Downs, ‘Fair Game: Exploitative Role-Myths and the American Opium Trade’, Pacific Historical Review, vol. 41, no. 2, 1972.

6John D. Wong, Global Trade in the Nineteenth Century: The House of Houqua and the Canton System, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

7For the concept of ‘super exploitation’, see Ray Mauro Marini, Dialéctica de la dependencia [Dialectics of Dependency], (México, DF: Ediciones Era, 1973), 91–99.

8Unless otherwise indicated, figures are compiled from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reporting over the past twenty years across multiple countries and market levels. They are indicative snapshots rather than current prices.

9Adam Isacson, ‘Crisis and Opportunity: Unravelling Colombia’s Collapsing Coca Markets’, Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), 24 August 2023, https://www.wola.org/analysis/crisis-opportunity-unraveling-colombias-collapsing-coca-markets/.

10United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Global Report on Cocaine 2023: Local Dynamics, Global Challenges, United Nations, March 2023, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/cocaine/Global_cocaine_report_2023.pdf.

11UNODC, World Drug Report 2004, Volume 2: Statistics, United Nations, 2004, https://www.unodc.org/pdf/WDR_2004/Chap5_coca.pdf.

12For a more detailed exploration of this point, see Cecilia González, Narcosur: La sombra del narcotráfico mexicano en la Argentina [Narcosur: The Shadow of Mexican Drug Trafficking in Argentina] (Buenos Aires: Marea Editorial, 2014); Política de Drogas no Brasil: Conflictos e Alternativas [Drug Policy in Brazil: Conflicts and Alternatives], ed. Beatriz Caiuby Labate and Thiago Rodrigues (Campinas & São Paulo: Mercado de Letras, 2018); and Nick Reding, Methland: The Death and Life of an American Small Town (New York: Bloomsbury, 2009).

13 The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo, FARC-EP) emerged in the mid-1960s as a Marxist-Leninist guerrilla organisation rooted in peasant self-defence and struggles over land. Its programme centred on agrarian reform and a broader project of political and social transformation in a country marked by extreme land concentration and political exclusion. It became one of the principal insurgent forces in Colombia’s internal armed conflict, which also involved the state security forces and right-wing paramilitary groups.

14Alfred McCoy, The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (New York: Harper and Row, 1972); Gary Webb, Dark Alliance: The CIA, the Contras, and the Crack Cocaine Explosion (New York: Seven Stories Press, 1998); Ioan Grillo, Gangster Warlords: Drug Dollars, Killing Fields, and the New Politics of Latin America (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2016). For declassified documentation on the interlink between the cartels and the warfare state, see Peter Kornbluh and Malcolm Byrne, eds., The Iran-Contra Scandal: The Declassified History (New York: The New Press, 1993).

15Douglas Valentine, The CIA as Organised Crime: How Illegal Operations Corrupt America and the World (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2017); Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Inspector General, Report of Investigation: Allegations of Connections Between CIA and the Contras in Cocaine Trafficking to the United States, vols. I and II (Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Inspector General, 1998). Essential reading is Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St. Clair, Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs, and the Press, (London: Verso, 1999).

16Diana Marcela Rojas Rivera, El Plan Colombia. La intervención de Estados Unidos en el conflicto armado colombiano (1998-2012) [Plan Colombia: United States Intervention in the Colombian Armed Conflict (1998–2012)] (Bogotá: IEPRI-Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2015).

17Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, ‘The Empire’s Dogs Are Barking at Venezuela’, red alert no. 20, 6 November 2025, https://thetricontinental.org/red-alert-20-venezuela/; Pino Arlacchi, ‘The Great Hoax Against Venezuela: Oil Geopolitics Disguised as “War on Drugs”’, Venezuelaanalysis, 2 September 2025, https://venezuelanalysis.com/opinion/the-great-hoax-against-venezuela-oil-geopolitics-disguised-as-war-on-drugs/.

18Charlie Savage, ‘Justice Dept. Drops Claim That Venezuela’s ‘Cartel de los Soles’ Is an Actual Group’, The New York Times, 5 January 2026, https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/05/us/trump-venezuela-drug-cartel-de-los-soles.html.

19United States Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Forensic Sciences, Special Testing and Research Laboratory, ‘CY 2024 Annual Cocaine Report’, PRB no. 2025-42, 2025, accessed 6 January 2026, https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2025-09/CY2024%20Annual%20Cocaine%20Report%20PRB-2025-42%20Final.pdf; Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, ‘How Many International Laws Can the United States Break Against Venezuela and Still Get Away with It?: The Second Newsletter (2026)’, 8 January 2026, https://thetricontinental.org/newsletterissue/venezuela-us-attack/.

20Jason Hickel et al., ‘Imperialist Appropriation in the World Economy: Drain from the Global South Through Unequal Exchange, 1990–2015’, Global Environmental Change 73, no. 113823 (2022): 1 and 6, https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/113823/1/1_s2.0_S095937802200005X_main_1_.pdf.

21Guillermo Vázquez del Mercado, Ruggero Scaturro, and Alex Goodwin, Measuring the Scope and Scale of Illicit Arms Trafficking (Geneva: Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, January 2025): 2, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Measuring-the-scope-and-scale-of-illicit-arms-trafficking-GI-TOC-January-2025.v2-.pdf; UNODC, ‘Drug Trafficking: A $32 Billion Business Affecting Communities Globally’, accessed 4 November 2025, https://www.unodc.org/southasia/frontpage/2012/August/drug-trafficking-a-business-affecting-communities-globally.html; Financial Action Task Force, Money Laundering from Environmental Crimes (Paris: Financial Action Task Force, 2021): 10, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/money-laundering-environmental-crime.html; International Labour Organisation, ‘ILO Says Forced Labour Generates Annual Profits of US$ 150 Billion’, 20 May 2014, https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/ilo-says-forced-labour-generates-annual-profits-us-150-billion; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ‘Global Trade in Fake Goods Reached USD 467 Billion, Posing Risks to Consumer Safety and Compromising Intellectual Property’, 7 May 2025, https://www.oecd.org/en/about/news/press-releases/2025/05/global-trade-in-fake-goods-reached-USD-467-billion-posing-risks-to-consumer-safety-and-compromising-intellectual-property.html; UNODC, ‘Drug Trafficking: a $32 billion Business Affecting Communities Globally’, UNODC South Asia, 2012, https://www.unodc.org/southasia/frontpage/2012/August/drug-trafficking-a-business-affecting-communities-globally.html.

22United Nations Office on Drug and Crime Studies and Threat Analysis Section, Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs, Estimating Illicit Financial Flows from Drug Trafficking and Other Transnational Organised Crimes (Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, October 2011), 7 and 10, https://info.publicintelligence.net/UNODC-IllicitFlows.pdf.

23UNODC, Crime-related Illicit Financial Flows: Latest Progress (Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, December 2023), https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/IFF/2023/IFFs_Estimates_Report_2023-final-11dec2023.pdf.

24Office of the President of Colombia, ‘El 75 por ciento de la inversión extranjera directa que llegó a Colombia en 2024 beneficia a sectores no minero energéticos’ [Seventy-Five Percent of Foreign Direct Investment in 2024 Went to Non-Mining and Energy Sectors in Colombia], press release, 27 March 2025, https://www.presidencia.gov.co/prensa/Paginas/El-75-por-ciento-de-la-inversion-extranjera-directa-que-llego-a-Colombia-250327.aspx.

25 Hawala and hundi refer to informal value-transfer systems in which brokers (hawaladars) move money across borders through networks of counterparties rather than through formal bank transfers. A sender gives funds to a broker in one location, and a partner broker pays the recipient elsewhere; the brokers later settle accounts through off-setting transactions (trade invoices, cash couriers, or other balancing arrangements). These systems are widely used for legitimate remittances where formal banking is limited, but they can also be exploited to evade capital controls and anti-money-laundering oversight.

26UNODC, Research and Trend Analysis Branch and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Development Statistics and Information Branch, Conceptual Framework for the Statistical Measurement of Illicit Financial Flows (Vienna and Geneva: United Nations Office on Drug and Crime and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, October 2020), https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/IFF/IFF_Conceptual_Framework_for_publication_15Oct.pdf.

27UNODC, Estimating Illicit Financial Flows from Drug Trafficking, 5.

28HSBC Holdings plc., Interim Report 2025, approved 30 July 2025, https://www.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/sehk/2025/0822/2025082200025.pdf.

29Chris Blackhurst, Too Big to Jail: Inside HSBC, the Mexican Drug Cartels and the Greatest Banking Scandal of the Century (London: MacMillian, 2023).

30Financial Action Task Force, International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism and Proliferation (Paris: Financial Action Task Force, 2012–2025), https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/Fatfrecommendations/Fatf-recommendations.html.

31Mirko Nazzari and Peter Reuter, ‘How Well Does the Money Laundering Control System Work?’, in Crime and Justice, edited by Michael Tonry (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 3 July 2025).

32UNODC Regional Office for Afghanistan, Central Asia, Iran and Pakistan, ‘Improving regional investigations on money laundering and asset recovery’, accessed 6 January 2026, https://www.unodc.org/roca/en/NEWS/news_2024/november/improving-regional-investigations-on-money-laundering-and-asset-recovery.html.

33Ariadna Eljuri, ‘Gustavo Petro en la ONU: “La guerra contra las drogas ha fracasado”’ [‘Gustavo Petro at the UN: “The War on Drugs Has Failed”’], Últimas Noticias, 20 September 2022, https://ultimasnoticias.com.ve/general/gustavo-petro-en-la-onu-la-guerra-contra-las-drogas-ha-fracasado/; our translation.

34Richard Nixon, ‘President Nixon Declares Drug Abuse “Public Enemy Number One”’ (YouTube video, 17 June 1971), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8TGLLQlD9M.

35United Nations, Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961 (New York: United Nations, 30 March 1961), https://www.unodc.org/pdf/convention_1961_en.pdf.

36Karen Jessenia Gutiérrez Alfonso, ‘La Criminalización de los Cultivadores como Coartada Imperialista: Economía Política de las Drogas en Colombia’ [Addicted to Imperialism: The Criminalisation of Cultivators as an Imperialist Pretext: The Political-Economy of Drugs in Colombia], Adictos al imperialismo: Estados Unidos y la política de ‘guerra’ contra las drogas no. 1 [Addicted to Imperialism: The United States and the Politics of the ‘War’ on Drugs no. 1] (Buenos Aires: Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research; Bogotá: Centro de Pensamiento y Diálogo Político (CEPDIPO), October 2024), 11, https://thetricontinental.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Adictos-al-Imperialismo_Cuaderno-1_Web-1.pdf.

37Comisión de la Verdad, ‘La masacre de las bananeras’ [The Banana Massacre], No Matarás, Comisión de la Verdad, 22 December 2025, https://www.comisiondelaverdad.co/la-masacre-de-las-bananeras; Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (CNMH), ‘21 años de la masacre de Mapiripán’ [21 Years Since the Mapiripán Massacre], Noticias CNMH, 11 July 2018, https://centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/21-anos-de-la-masacre-de-mapiripan/.

38Catherine Le Grand, Colonización y protesta campesina en Colombia (1850-1950) [Colonisation and Peasant Protest in Colombia (1850–1950)] (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1988); Absalón Machado, El problema de la tierra: conflicto y desarrollo en Colombia [The Land Problem: Conflict and Development in Colombia] (Bogotá: Debate, Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, 2017); and Alejandro Reyes Posada, Guerreros y campesinos: El despojo de la tierra en Colombia [Warriors and Peasants: The Dispossession of Land in Colombia] (Bogotá: IES, CINEP, 2010).

39Leandro Ramos Castiblanco, Formas de violencia urbana populares: monografías barriales Bogotá, Medellín y Cali [Forms of Popular Urban Violence: Neighbourhood Monographs from Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali] (Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia, 2021).

40National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), Government of Colombia, Tercer Censo Nacional Agropecuario 2014: Hay Campo para Todos: La mayor operación estadística del campo colombiano en los últimos 45 años [Third National Agricultural Census 2014: Is There Land for Everyone: The Largest Statistical Operation of the Colombian Countryside in the Last 45 Years] (Bogotá: DANE, 2014), https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/agropecuario/censo-nacional-agropecuario-2014.

41UNODC, Colombia: Monitoreo de los territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2017 [Colombia: Monitoring of Territories Affected by Illicit Crop Cultivation 2017] (Bogotá: UNODC-SIMCI, Septembet 2018), 33, https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Colombia_Monitoreo_territorios_afectados_cultivos_ilicitos_2017_Resumen.pdf.

42Karen Jessenia Gutiérrez Alfonso, ‘La criminalización de los cultivadores como coartada imperialista’, 68; our translation.

43Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, ‘What Is the Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)?’, accessed 4 November 2025, https://ophi.org.uk/what-global-mpi.

44UNODC and Fundación Ideas para la Paz, ¿Quiénes Son las Familias que Viven en las Zonas con Cultivos de Coca? Caracterización de las Familias Beneficiarias del Programa Nacional Integral de Sustitución de Cultivos Ilícitos (PNIS) [Who Are the Families Living in Areas with Coca Crops? Characterisation of the Families Benefiting from the National Comprehensive Programme for the Substitution of Illicit Crops (PNIS)] (Bogotá: UNODC and Fundación Ideas para la Paz, August 2018), https://www.unodc.org/documents/colombia/2018/Agosto/Quienes_son_las_familias_que_viven_en_las_zonas_con_cultivos_de_coca_N.1.pdf.

45Karen Jessenia Gutiérrez Alfonso, ‘La criminalización de los cultivadores como coartada imperialista’, 72; our translation.

46Karen Jessenia Gutiérrez Alfonso, ‘La criminalización de los cultivadores como coartada imperialista’, 70; our translation.

47Los orígenes de la cocaína: Colonización y desarrollo fallido en los Andes amazónicos [The Origins of Cocaine: Colonisation and Failed Development in the Amazonian Andes], ed. Paul Gootenberg and Liliana M. Dávalos (Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes-Facultad de Economía, Centro de Estudios sobre Seguridad y Drogas (CESED) and Ediciones Uniandes, 2021).

48United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention, Tendencias Mundiales de las Drogas Ilícitas [World Illicit Drug Trends] (Vienna: United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention, 2001), https://www.unodc.org/pdf/report_2001-06-26_1_es/report_2001-06-26_1_es.pdf. Using the World Bank’s WDI definition of agricultural land (arable land + permanent crops + permanent pastures), Colombia had about 448,590 sq km of agricultural land in 2000 (that is 44,859,000 hectares).

49Karen Jessenia Gutiérrez Alfonso, ‘La criminalización de los cultivadores como coartada imperialista’, 23; our translation.

50Karen Jessenia Gutiérrez Alfonso, ‘La criminalización de los cultivadores como coartada imperialista’, 74; our translation.

51Government of Colombia and FARC-EP, Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace, 24 November 2016 (English translation), (Indiana: Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame: 24 November 2016), https://peaceaccords.nd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Colombian-Peace-Agreement-English-Translation.pdf.

Far from tackling the narcotics trade, the War on Drugs has become an imperial tool to discipline defiant governments and advance counterrevolutionary agendas. Campesinos and the working class pay the price, while capital reaps the profits. Read More