On a typical evening in the heart of Paris, Taha Siddiqui can be found at his bar, greeting customers and pouring drinks. During busy nights, he’s organizing events there, with an Afghan poet reading her work, anti-war Russian musicians in a punk band, or a director sharing their documentary — all, like him, finding refuge in France. But long before he became a bar owner, Siddiqui was one of Pakistan’s most high-profile investigative journalists, determined to expose corruption and government abuses. In 2018, after narrowly escaping a kidnapping and attempted assasination he believes was carried out by Pakistan’s army, he fled to Paris, where he has lived in exile ever since.

Siddiqui now channels his energy into the Dissident Club, a bar and community space he opened in 2020. Described as a “21st-century café littéraire,” it has become a bustling cultural hub for exiled journalists, whistleblowers, and dissidents from around the world; to date, dissenters from over 50 countries, including Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, Belarus, Mexico, Egypt, Russia, and China have visited or hosted events at the club. Activities include film screenings, book launches, poetry readings, art showings, comedy open mics, and panel discussions on human rights. The bar also hosts popular local jazz acts to help subsidize its programming.

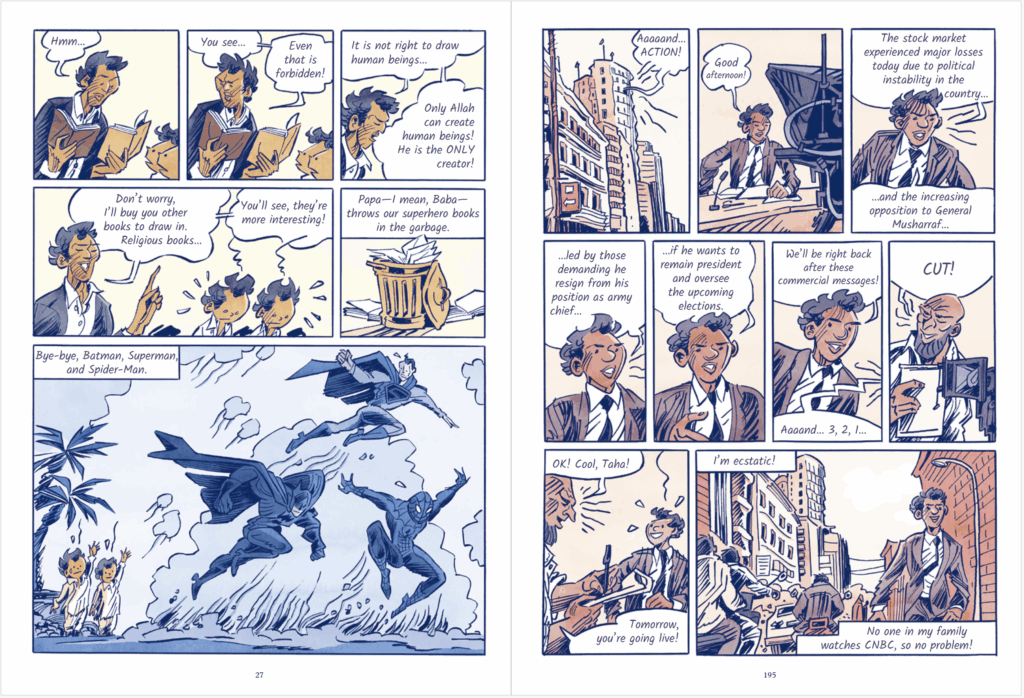

In addition to running the bar, Siddiqui continues to speak out on press freedom, Pakistani politics, and the challenges of living in exile. His recently published graphic memoir, “The Dissident Club,” recounts his journey from a strict Islamist upbringing in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan to his career as a journalist and the beginnings of his life in Paris. Curious and questioning as a child, Siddiqui often clashed with the dogma of his family’s fundamentalist beliefs — tensions that he says pushed him toward journalism as a way of interrogating authority and exposing abuses of power. Today, he provides political commentary for French media outlets and teaches journalism at various universities , all while curating a space for others who have also been forced to leave home.

For Siddiqui, the work is deeply personal. He sees the Dissident Club as a refuge where dissenters can find strength and solidarity with one another, countering the isolation often imposed on them through forced relocation in exile, the threat of surveillance, and transnational repression — all obstacles Siddiqui has had to face. This mission reflects his own trajectory: Pakistan remains one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, ranked 158th out of 180 in Reporters Without Borders’ 2025 Press Freedom Index, a drop of six places from last year.

Central to all these activities is Siddiqui’s refusal to be silenced or intimidated, and his belief that dissidents are ultimately safer when they band together. At the center of the Dissident Club stands a red pillar with a Leonardo da Vinci quote written in white paint: “Nothing strengthens authority so much as silence.”

Siddiqui spoke to Nieman Reports about his memoir, opening the Dissident Club, restarting his life in Paris, and how he keeps the bar running despite the challenges and pushback.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The post Welcome to the Dissident Club appeared first on Nieman Reports.

On a typical evening in the heart of Paris, Taha Siddiqui can be found at his bar, greeting customers and pouring drinks. During busy nights, he’s organizing events there, with an Afghan poet reading her work, anti-war Russian musicians in a punk band, or a director sharing their documentary — all, like him, finding refuge in France. But long before he became a bar owner, Siddiqui was one of Pakistan’s most high-profile investigative journalists, determined to expose corruption and government abuses. In 2018, after narrowly escaping a kidnapping and attempted assasination he believes was carried out by Pakistan’s army, he fled to Paris, where he has lived in exile ever since. Siddiqui now channels his energy into the Dissident Club, a bar and community space he opened in 2020. Described as a “21st-century café littéraire,” it has become a bustling cultural hub for exiled journalists, whistleblowers, and dissidents from around the world; to date, dissenters from over 50 countries, including Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, Belarus, Mexico, Egypt, Russia, and China have visited or hosted events at the club. Activities include film screenings, book launches, poetry readings, art showings, comedy open mics, and panel discussions on human rights. The bar also hosts popular local jazz acts to help subsidize its programming. In addition to running the bar, Siddiqui continues to speak out on press freedom, Pakistani politics, and the challenges of living in exile. His recently published graphic memoir, “The Dissident Club,” recounts his journey from a strict Islamist upbringing in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan to his career as a journalist and the beginnings of his life in Paris. Curious and questioning as a child, Siddiqui often clashed with the dogma of his family’s fundamentalist beliefs — tensions that he says pushed him toward journalism as a way of interrogating authority and exposing abuses of power. Today, he provides political commentary for French media outlets and teaches journalism at various universities , all while curating a space for others who have also been forced to leave home. Excerpts from “The Dissident Club,” Taha Siddiqui’s graphic memoir about his childhood and career as an investigative journalist. Siddiqui says his memoir is a personal “act of resistance” drawn in comic book form because his parents forbade “pictorial books” at home growing up. Courtesy of Taha Siddiqui and Arsenal Pulp Press. Illustrations by Hubert Maury. For Siddiqui, the work is deeply personal. He sees the Dissident Club as a refuge where dissenters can find strength and solidarity with one another, countering the isolation often imposed on them through forced relocation in exile, the threat of surveillance, and transnational repression — all obstacles Siddiqui has had to face. This mission reflects his own trajectory: Pakistan remains one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, ranked 158th out of 180 in Reporters Without Borders’ 2025 Press Freedom Index, a drop of six places from last year. Central to all these activities is Siddiqui’s refusal to be silenced or intimidated, and his belief that dissidents are ultimately safer when they band together. At the center of the Dissident Club stands a red pillar with a Leonardo da Vinci quote written in white paint: “Nothing strengthens authority so much as silence.” Siddiqui spoke to Nieman Reports about his memoir, opening the Dissident Club, restarting his life in Paris, and how he keeps the bar running despite the challenges and pushback. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. The post Welcome to the Dissident Club appeared first on Nieman Reports. Read More